Saying it’s been a wet winter is an understatement! It’s been terrible for archaeological excavations, with flooded sites, high water tables and mud, glorious mud! For Leicester Cathedral Uncovered, this has been a bit of a blessing, with staff, rained off other projects, devoting a considerable amount of their winter cleaning the skeletons from the Cathedral. They have done an amazing job and now 92% of the assemblage is ready for analysis (with the remaining skeletons expected to be finished in the forthcoming weeks). In this blog, excavation director Mathew Morris brings us up to date with work on the project.

The assessment of the materials recovered from the Cathedral excavation is progressing rapidly and over the next few months we will have blogs from our different specialists, each taking a more detailed look at their areas of work. This assessment needs to establish the significance of the material being looked at. It is, therefore, important to be able to identify where it all fits in the site’s stratigraphic sequence (the chronological order of the archaeology). This relies on the accuracy of the on-site recording and the ability to reconstruct the site digitally after the excavation has finished.

Altogether, 1,791 unique features and layers were recorded during the excavation (in addition to the 1,237 skeletons). Each of these has a context sheet, the written record providing the description and interpretation of the feature, its relationship with surrounding contexts, what finds were recovered from it and references to other records. Each context also has photographs and drawings and/or a 3D model (created using structure-from-motion photogrammetry), as well as survey co-ordinates tying it into the Ordnance Survey National Grid. Each skeleton has a similar set of records too. This is a lot of data to process and a database is a key first step in the post-excavation process, giving everyone access to the cross-referenced records.

From here we can start digitally rebuilding the site. Central to this is constructing a Harris Matrix, a diagram showing the temporal succession of the contexts (from oldest at the bottom to youngest at the top) and thus the sequence of deposition, construction, grave digging and other activities on the site. As more data is fed back from the specialists, this diagram can be fine-tuned and divided into chronological phases, breaking up the data into smaller, more manageable chunks from which the story of the site can be revealed.

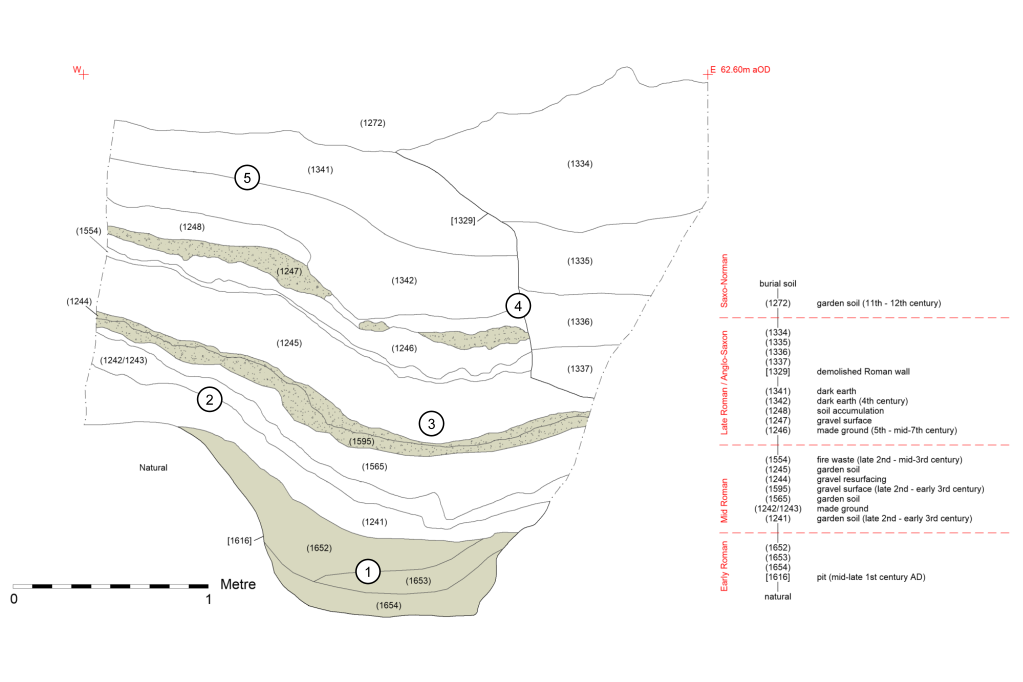

Take this photograph and drawing. They show a cross-section through the different layers beneath the burial soil in one area of the site, down to the natural (geological) ground level; the diagram to the right of the drawing is its Harris Matrix.

This shows an incredible sequence of archaeology spanning some 1,100 years from the latter half of the 1st century AD through to the early 12th century.

- At the bottom of the sequence is a pit [1616]. This was dug into the natural ground during the early Roman period (sometime in the mid-late 1st century AD), probably to quarry the sand and gravel for construction material. Over time it has weathered and filled in.

- Overlying the pit is a succession of garden soils interleaved with gravelled yard surfaces and other evidence of nearby habitation. These date from the later 2nd century through to the 4th century and show that this area remained an external space throughout the Roman period, sometimes under cultivation and at other times in use as a gravelled yard area.

- The early pit has created a lot of problems throughout the Roman period, causing subsidence in the overlying layers.

- The higher gravel surface (1247) appears to be contemporary with a stone wall [1329], probably a boundary wall between properties. At a later date, sometime after the Roman period, the wall was demolished and all of its stonework removed. This is typical of Roman buildings in Leicester, which became a good source of recycled building material in the medieval period. It is even possible that this wall was demolished to make way for St Martin’s Church, or recycled to build the original church building.

- From the 4th century onwards, thick layers of soil continued to form across the area. It is unclear at the minute whether these soils represent habitation, cultivation or abandonment of the area but as we gather more data this will become clearer. Finally, the area was incorporated into the church’s burial ground in the early 12th century. It remained part of the burial ground until, in 1939, the Old Song School was built on the site.

This is just a quick interpretation of one drawing, of many, but already we can see a story of changing land use over two millennia starting to emerge, and we have a framework in which we can place all our other evidence, be it pottery, animal bone, environmental remains or more unique artefacts likes coins, brooches and hair pins. This is also why we are so careful to make detailed records of the archaeology as we dig it. Excavation is inherently destructive and at the end of the process the paperwork and the finds are the only material record of what was once there.

The Leicester Cathedral Revealed project has been made possible thanks to the National Lottery Heritage Fund and National Lottery players. Find out more about the project at https://leicestercathedral.org/