The history of Leicester contains a great variety of different stories, peoples, and historical events. Archaeologist Joshua Cattermole investigates the Tudor town’s links with the Republic of Venice.

During the transition from the medieval to modern era we see much tumult, including some of the great national events of the age: the Wars of the Roses, the fall of Richard III and the ascent of the Tudor dynasty, as well as the Dissolution of the Monasteries. We also sometimes see evidence of international influence, highlighting just how interconnected Europe was 500 years ago. Often this evidence is reserved for the realm of politics, be it international treaties or discourses between monarchs. Foreign influence at a local level is rarely seen, so it is a rare pleasure to find it in the archaeological record, especially in Leicester. This is embodied in a fascinating discovery of a tiny silver soldino from the Republic of Venice – found at a site on the corner of Highcross Street and Vaughan Way (excavated in 2017), where the Wullcomb apartment complex now stands next to the John Lewis car park.

This small piece of silver, measuring 12mm in diameter and weighing 0.3g, was minted in the city of Venice during the reign of Agostino Barbarigo, who served as Doge, or ruler, of the Republic from 1486-1501. This example was minted in the year of his death, 1501, by the mint master Stefano Ferro. The mint master oversaw minting operations within the mint at Venice, which was situated in the centre of the city, opposite the palace of the Doge and the great basilica of St Mark.

At that time, the Republic of Venice, arguably the greatest mercantile power of the medieval and early modern period, was at its zenith, holding sway over large tracts of north-eastern Italy, territories in Greece, as well as great influence amongst the trading cities of the Levant. Extensive political and mercantile connections across Europe guaranteed that no lucrative opportunity would pass unnoticed and it was often the go-to power when it came to the trade of luxury goods, such as silks, fine wines, glassware, printed books and manuscripts. The city itself was also one of the grandest in Europe, with a population of near 200,000 people (compared to Leicester’s 4,000), decorated with great monuments, patron of artists, and the centre of European book production.

The powers of Europe always considered Venice when they required such finery to whet the appetites of their upper classes, and the Kingdom of England was no exception. Newly crowned King Henry VII was keen to cultivate good relations with the Venetian merchants who traded in his cities. By this time a Venetian ambassador resided in London, with Venetian imports arriving almost exclusively through the port of Southampton.

Once a year a great fleet of galley ships would leave Venice for north-western Europe, with the larger part docking in England. Despite the desire of the English authorities to bring in luxury goods, naturally such incomers from a far-away land generated tension with their English hosts, and disputes were not unheard of. However, King Henry would go out of his way to side with the Venetians, and shower them with favours. This is highlighted by an invitation extended by the king to the Venetian noblemen of the fleet to dine with him at Richmond Palace in 1506.

But how does a silver coin found in Leicester fit into this grand narrative of trade and politics?

Venetian ambassadors across Europe would keep tabs on how the Republic could best profit from any opportunity on the continent and beyond, so when it arose that there was a shortage of small change in England they pounced at the chance for profit. This, coupled with the high favour which Venice had in England, allowed them to import large numbers of silver soldini, with Venice profiting from the exchange rate. The soldino was about the same size and weight as a contemporary English clipped penny or halfpenny, so could fit easily into the monetary system of a country starved of the smaller denominations people needed to make day-to-day purchases.

Coincidentally, the same phenomenon had occurred a century earlier, in the years 1400-1416, until a combination of government pressure and a reform to the English currency saw the Venetian coins eradicated. Again, in the 1470s-1490s, small numbers of soldini entered circulation, and mass imports of the latest type of soldino, introduced in 1499, arrived in England, probably with the galley fleet of the year 1500; seeing instant success with the population, who were grateful for money to conduct daily transactions.

The English government did not initially oppose the reintroduction of the soldino, clearly, as there was no legislation against them, unlike their first incursion in the previous century. The favour of Venice being paramount, no action was taken, and so soldini would arrive in large numbers, until the War of the League of Cambrai forced the suspension of the annual galley fleets in 1509. The fleets resumed in 1518, along with further exportation of soldini, though the poor quality of the goods aboard disappointed the new King Henry VIII and his advisor Cardinal Wolsey. Further fleets were a disappointment, and in 1532, following an ultimatum by the king, the last state-sponsored Venetian galleys left Southampton, and England, behind them. By this point the soldino had largely been driven from circulation by legislation, as well as changes to the weight standards of the English currency, and any survivors will have disappeared following the Great Debasement of the coinage in 1544.

During the period of the soldino in England they spread far and wide, filling the gaps where English silver was lacking in the money pouches of everyday people. Though they predominately arrived through Southampton, and through London in smaller numbers, they spread from these areas around the country.

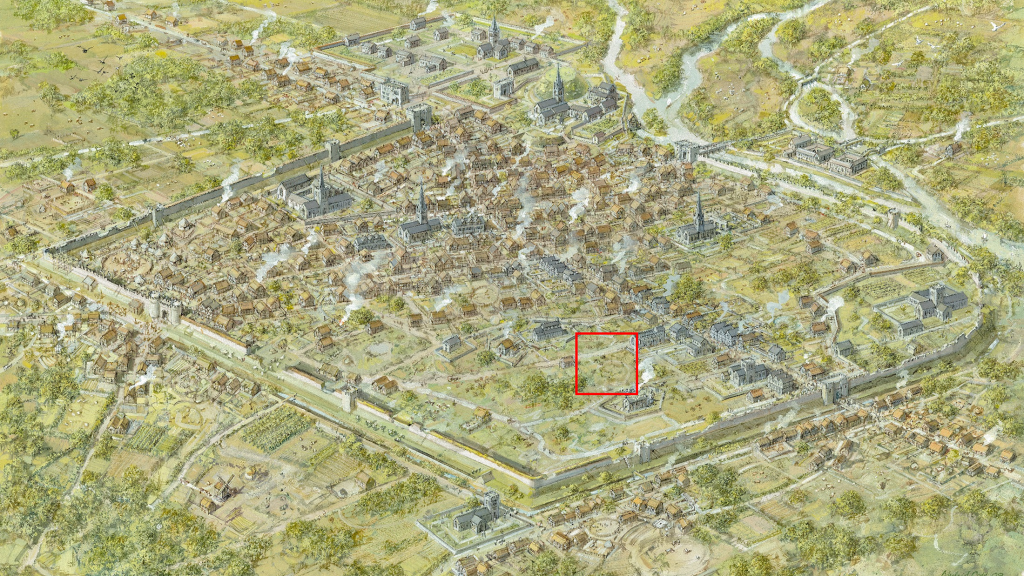

Leicester was no exception, as is clearly shown by the discovery of the Barbarigo soldino. At the time of circulation, the area of the town where it was found had declined from former prosperity, and much of the land had ceased occupation. Instead, the area was turned over to cultivation, consisting of gardens and orchard plots for properties facing onto St John’s Lane (later known as Causeway Lane). There was activity at the nearby St John’s Hospital, built in the 12th century, and the Shirehall, built in the mid-14th century, but otherwise it was a relatively quiet area, and the coin probably represents a casual loss.

Nevertheless, It is quite fascinating how a tiny silver coin minted in one of Europe’s great cities could find its way to a quiet corner of the small provincial town of Leicester. This, more than anything, truly highlights how interconnected Europe, including Leicester, was five centuries ago.

Josh is an expert on Venetian soldini and has published Galley Pence (Vol. 1), which explores the arrival and circulation of soldini of the Republic of Venice into the Kingdom of England in the early 15th century. Find out more here.

Thank you for this insight into a fascinating small part of history of England and its connections with Europe. It contrasts greatly with the isolationism of our current government.

I’m ever grateful for the knowledge.