In this month’s instalment from Coventry Charterhouse we move clockwise around the footprint of the former monastery and move from the eastern range of cells to the southern range. Site director, Andrew McLeish tells us more…

While geophysical survey can often give us an idea of what might be under the ground it has its limitations, especially when a site is heavily disturbed by later activity, and we often find that we need to have an actual look at what is below the surface.

At the Charterhouse, any event held in the former cloister area can only ever have the Events marquee put up in one particular space. Why? Because the site is a Scheduled Monument and the archaeology below the ground has statutory protection to prevent damage to the fragile remains. The spot the marquee occupies is the only location where there is sufficient ground cover to be able to safely drive in the tent pegs without reaching the archaeology!

From east cloister to west cloister the archaeology goes from being immediately under the turf to 1m below the ground (in less than 40m), but why does it do this when most of the ground now is level? The answer lies (quite literally) in the changes made to the site since the monastery was first laid out. Visitors will notice that the modern topography slopes from the back of the gardens to the east range of cells, then levels out to the west range, then slopes down to the River Sherbourne. In monastic times this change would have been much more pronounced as the site was originally terraced, and the faintest suggestion of this can still be seen in the stepped boundary wall surrounding the existing site. In monastic times the east range of cells would have been higher than the west, with the southern range sloping down to meet them.

Post dissolution these sharp transitions were eased in the 18th century as the plant nursery brought in soil to bury the demolition rubble and lay out new level planting beds, then more as the Victorian garden took shape. Whilst today the level ground over the centre of the site owes its origins to the Coventry Bowling Club.

Visit Charterhouse today and you will see a large modern wall crossing the southern edge of the former Great Cloister. This will ultimately re-create the feel of the pentice walkway around the cloister and is absolutely slap bang on the alignment of the former monastic cloister wall (more on that in a future blog post…).

If you visited in the 1400s you’d be looking at a 12ft high sandstone wall with the roofs of the monks’ houses just poking over the top. In the covered walkway were the doorways and food hatches for the monks. Behind the wall were, we think, four cells with the extant medieval masonry wall at the southernmost end of the site forming the rear garden wall for the south range in monastic times.

With this in mind, the space behind this new wall is intended to be used by the new events venue in the Old Coach House and we needed to know at what depth the archaeology survived and its state of preservation, especially with it being in the protected area of the Scheduled Monument. This in turn would allow the building designs to be amended so that there was no damage to the underlying archaeology.

The titular two trenches were dug in September 2020 to investigate this area. Previous trenching in 2017 and 2019 had encountered small sections of surviving medieval structures here but had been insufficient to build a detailed picture of the layout of the south cloister cells.

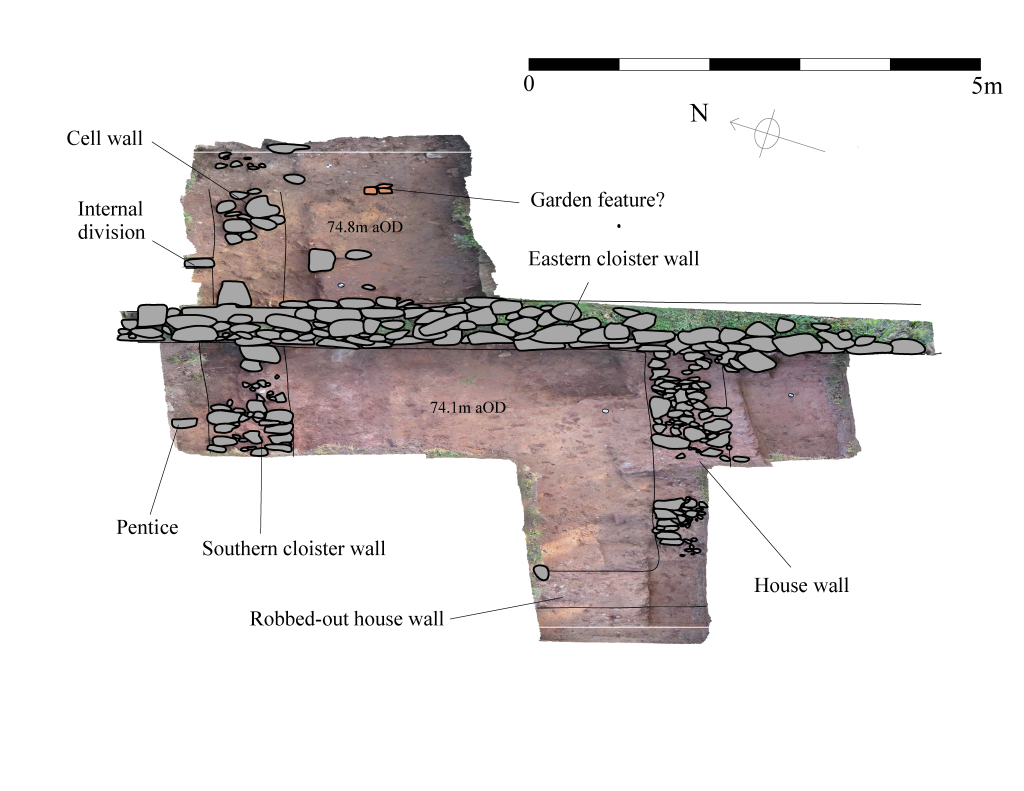

The first trench in 2020 (Trench 37) was laid out over the footprints of the two cells in the south-eastern corner of the Great Cloister. This uncovered the footings of the southern cloister wall, part of the pentice-covered cloister walk, as well as sufficient remains of a partially robbed out wall to determine the footprint of a monk’s house. A small extension to the trench on the eastern side of the extent eastern cloister wall revealed part of another cell wall and tiles which could relate to potential garden features, including a medieval floor tile with a 638-year-old badger pawprint preserved in its surface!

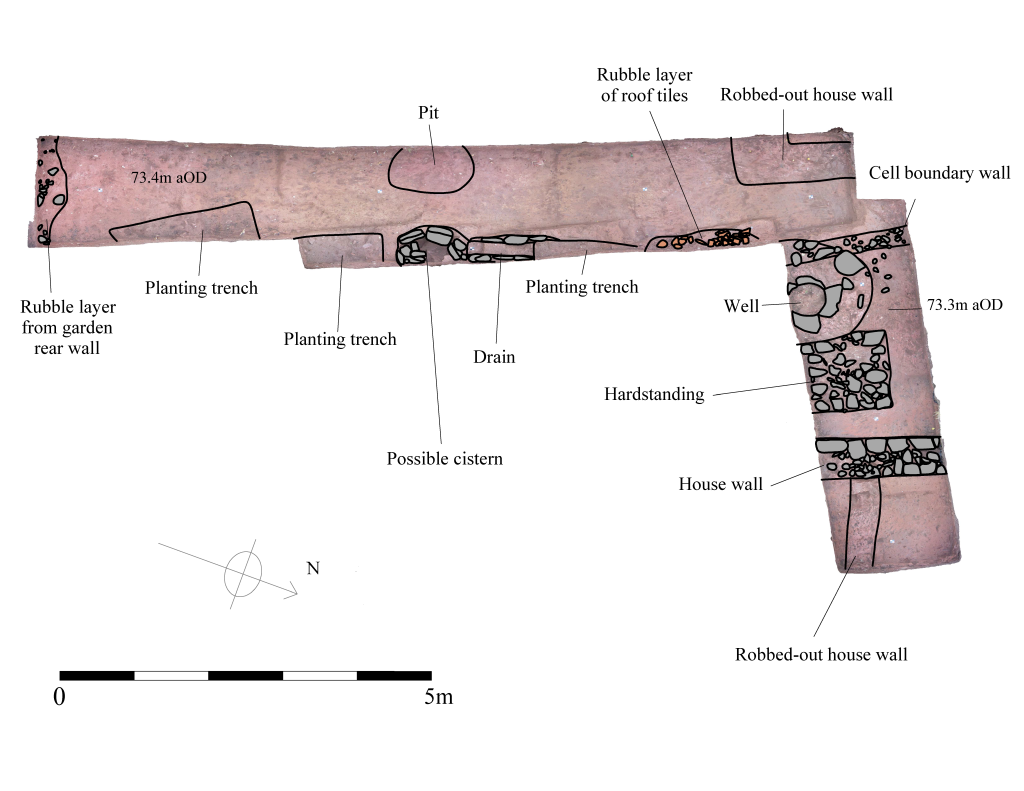

The second, Trench 38, dug to the west of the first, revealed the partial remains of two further monks’ houses and associated boundary walls and outdoor structural features. The easternmost house had surviving stone walls, which lined up with structures located in 2019, and an area of associated garden plot which contained a well-preserved stone well and surrounding hardstanding. Immediately to the west of the well was another stone wall which was the boundary between the two cell plots. West of that, in the corner of the trench was the corner of a further robber wall footing. From its alignment is was most likely to be the remains of another house. Whilst to south, in the area of the cell’s garden, protruding out from the trench’s eastern edge, was a possible cistern and its inlet drain.

So, what have we learned? In this area of the site, the monastic structures have been very disturbed by later activities, especially towards the south. However, the partially exposed footprints of the southern cells are still clear to see in these trenches. To the east, the archaeology is very shallow, just beneath the turf in places, whilst to the west it is deeper buried beneath demolition material and imported bedding soil.

Features inside the monks’ houses appeared to be completely destroyed. However, the two trenches dug in 2020 still revealed a wide range of new evidence about how the space was used in the Charterhouse’s southern range of cells. Of particular note, the presence of drains and a potential cistern underlying the projected course of a boundary wall between two of the cells is strong evidence for a pre-conceived drainage and water management system being constructed before the erection of the cell enclosures and their associated structures.

Finally, the presence of undisturbed demolition material covering areas of these trenches also means that there is good potential for further medieval features, sealed beneath the rubble, to survive intact. These could be investigated if ever any further opportunity to excavated these cells presented itself.

In the next blog we will shift away from open area excavations to look at different aspect of the archaeological process, including buildings archaeology and how it has been used to build our understanding of the history of Charterhouse’s surviving monastic and later buildings.

Find out more about the Coventry Charterhouse here.